Makerere University researcher and historian in the Department of History, William Musamba, has offered new insights into the historical tensions that continue to shape Busoga’s political identity and governance struggles.

His research titled “Rejected Homeland: Conflict and the Politics of Identity in Busoga, Uganda (1919–1960)” was presented as part of Makerere University’s PhD Completion Grant Initiative (2021–2025), led by the Directorate of Graduate Training. Now in its fourth year, the programme has supported 65 doctoral students to finalise and showcase their work, contributing to national development priorities through applied, locally relevant research.

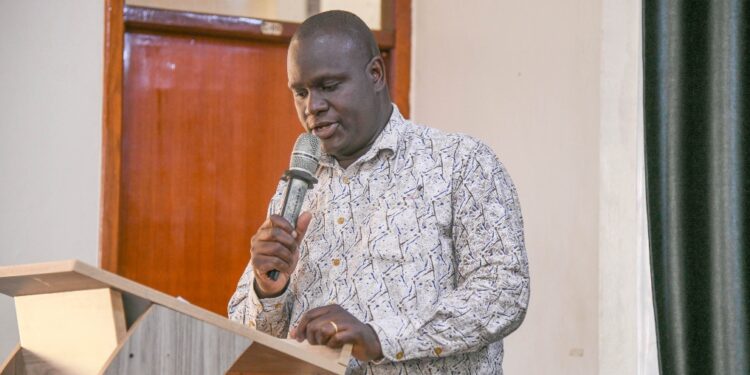

Speaking at the PhD Completion Grant Research Dissemination Workshop held at the School of Food Science, Conference Hall, Musamba shed light on how British colonial policies fostered deep political fragmentation in Busoga—once a strategic and economic hub in eastern Uganda, famously home to the source of the Nile.

“Despite its geographic centrality, Busoga has long been politically and culturally marginalized,” Musamba noted in the opening of the presentation. “My research asks why the region has struggled to maintain a coherent identity and political unity for over a century.”

Through a combination of archival research, colonial-era correspondence, and oral histories, Musamba traced the roots of division to early colonial strategies that imposed artificial ethnic categories and leadership structures.

One major source of contention was the creation of the Kyabazinga, a paramount chief, by British administrators—a position that lacked legitimacy among several clans in the region.

“Traditional authority in Busoga was plural and decentralized,” Musamba explained. “By imposing a centralized system of leadership, colonial rule disrupted the organic evolution of political institutions and deepened internal divisions.”

The study also highlights how rival Abataka (clan-based) associations in the 1920s and beyond clashed over who held the legitimate claim to represent Busoga. These groups often labeled each other “foreigners,” fueling identity-based conflict that persisted long after independence.

Musamba pointed to the 1963 Validation Act—which formally recognized the Kyabazinga institution—as a post-independence attempt to consolidate authority. However, he argued that the Act only reinforced existing divisions, turning what was intended to be a symbol of unity into a source of political alienation.

“The colonial and postcolonial state both failed to address the plural realities of Busoga’s internal politics,” he said.

The presentation drew attention not only to historical grievances but also to their modern-day implications. Musamba urged policymakers and scholars to consider how colonial legacies continue to shape regional governance and ethnic relations in Uganda.

“Understanding Busoga’s story is crucial for building more inclusive and legitimate governance structures,” he said. “This case offers valuable lessons for other multi-ethnic regions struggling with similar legacies.”

Musamba’s work forms part of a growing body of scholarship on postcolonial state formation and the contested role of traditional authority in East Africa. His published research includes articles in the African Humanities Texts and the Socio-Economic Studies Journal, as well as a widely read academic blog on historical research in Uganda.

The presentation ended with a call for deeper engagement with historical narratives in shaping modern policy. “We must learn from the past if we want to build a more equitable future,” Musamba concluded.