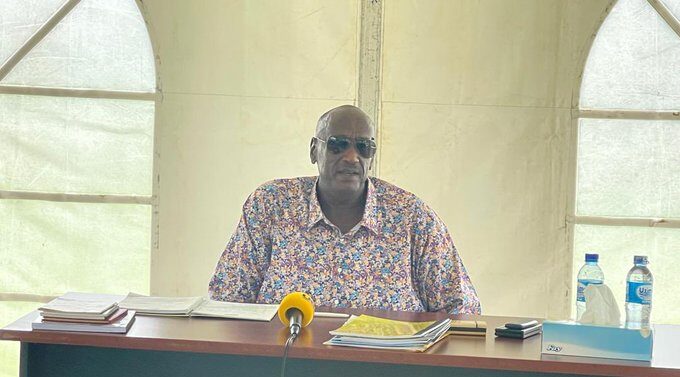

General Caleb Akandwanaho, popularly known as Salim Saleh, on Thursday delivered a resounding call for comprehensive land reforms during the Musevenomics 2025 Conference held at Mestil Hotel, describing Uganda’s distorted land market as “the most constrained factor of production” and a major obstacle to inclusive economic transformation.

Speaking in his capacity as Chief Coordinator of Operation Wealth Creation (OWC) and Chairman of the Uganda Development Forum, Gen Saleh expressed appreciation to partners who have supported OWC over the last decade and reiterated his commitment to deepening economic inclusion.

“Over the past 10 years, we have made a strong contribution in moving people into the money economy,” said Gen Saleh. “We commit to doing even more in the next 5–10 years.”

But his tone quickly turned serious as he addressed what he sees as a persistent crisis in Uganda’s land governance. “Today, we continue to operate within a constrained land market,” he warned. “This limitation stifles growth, delays investment, and entrenches poverty among our people.”

He emphasised the need to “liberate the land market” through functional, equitable, and inclusive reforms that prioritise the rural poor, women, and youth. “Land is the premier factor of production. Without secure, accessible land systems, no meaningful development can occur,” Gen Saleh asserted.

The Stimulus That Cannot Work Without Land

Gen Saleh argued that most economic stimulus programmes rely on land, yet the sector remains the least reformed and most distorted. Drawing on inputs from technical experts and advisors, he highlighted advisory notes, land audits, and the underutilization of large tracts of land, particularly those held in conservation or by government agencies.

“80% of the stimulus packages we have proposed are based on land,” he said. “If land is a distorted factor of production, then it distorts all other areas.”

One of the most revealing moments came when Gen Saleh referred to an advisory note from Dr Amanda Ngabirano, the Chairperson of the National Physical Planning Board.

“Do we understand the land use balance sheet in Uganda?” he asked, quoting her. “By 2040, when our population reaches 60 million, how will we feed our people if we don’t fix land use today?”

He also highlighted the underperformance of over 4 million acres of land currently under conservation or held in trust by various government agencies. “Some agencies holding land in trust are not maximising its usage and, in some cases, they’re even creating conflicts over that land,” he added.

Who Owns Kampala?

Touching on a controversial and often whispered topic, Gen. Saleh disclosed he is funding a study titled “Who Owns Kampala?” to examine land ownership in Uganda’s capital. “Everybody thinks I own half of Kampala,” he joked. “But I think I own, at most, two acres.”

He revealed that internal security recently questioned his land ownership in Kapeeka, forcing him to defend himself with historic documentation and prior research. “Imagine ISO asking you how you came to own your land. Fortunately, we had already studied the ownership and utilisation history of the land,” he said.

The Mission to End Poverty

Reflecting on the past decade of Operation Wealth Creation, Gen Saleh shared that Uganda has successfully reduced the population outside the money economy from 68% to 39%.

“We were told to find people who had never touched money. It was not easy,” he said. “We worked through coffee, tea, and other inputs. Today, I hear poverty levels have also gone down.”

He tasked participants and economists attending the conference to focus on practical deconfliction of land, land audits, and better land use planning. “If we don’t resolve land distortions, we won’t achieve our goal of tenfold economic growth,” he cautioned. “Factories are built on land. Homesteads sit on land. And yet land remains the most distorted resource.”

A Call to Academia and Government

Gen Saleh urged Uganda’s think tanks, academia, and policymakers to urgently support comprehensive land research and planning. “Help us understand the land use balance sheet,” he implored. “If we do that, I believe we shall devise new means of utilising this resource maximally.”

He closed his remarks with a tribute to his colleagues in government and civil society and hinted at a collaborative effort to document Uganda’s economic history, from the 1946 protectorate plan to the 1996 liberalisation era.

“We are trying to compile Uganda’s economic history. And the more we read, the more we understand that land is central to it all,” he said.