After more than two decades of waiting, hope has finally returned to hundreds of families in Mubende district who lost their ancestral land in 2001 to pave the way for the German-owned Kaweri Coffee Plantation.

In a historic milestone, compensation payments have officially begun reaching the affected residents of Kitemba, Kijunga, Kilyamakobe, and Luwunga villages, marking a hard-fought victory for land justice in Uganda.

The compensation comes after years of relentless legal battles, community mobilisation, and unwavering support from civil society organisations. ActionAid International Uganda, together with the Network for Public Interest Lawyers (NETPIL) and FIAN Uganda, played a pivotal role in supporting the evictees with legal aid and advocacy.

A Struggle That Refused to Die

In August 2001, 401 families were evicted from over 12 square miles of land in Mubende district. The eviction was carried out by armed security officers and left residents homeless, landless, and economically crippled. The land was handed over to the Neumann Kaffee Gruppe, a German investor, for the establishment of the Kaweri Coffee Plantation, without proper consultation or compensation for the residents.

The displaced families, many of whom had lived on the land for generations, led by a retired teacher, Baleke Kayiira Peter, and Mubende Assistant Resident District Commissioner (RDC) Musindi Andrew Solomon, formed a collective, joined forces and began a long legal battle against the Attorney General and the coffee investors.

“With the support of ActionAid Uganda and other partners, the evictees filed a legal suit in 2001 before the High Court Land Division in Kampala,” stated lawyer Kange Veronica from the Network of Public Interest Lawyers (NETPIL). Over the next two decades, the case would take several legal turns.

Beginning of Justice

High Court Judge Justice Anup Singh Choudry delivered his ruling on March 28, 2013. In this landmark decision, he found that the plaintiffs—over 2,000 residents forcibly evicted from their land in Mubende District in 2001—had been unlawfully displaced without adequate compensation. He ordered approximately €11 million (about Shs37bn at the time) in compensation to be paid to the evictees.

However, the judgment did not hold Kaweri Coffee Plantation Ltd. or the Ugandan government directly liable for the compensation. Instead, Justice Choudry assigned responsibility to the lawyers representing the Uganda Investment Authority, citing their alleged misadvice to the government regarding the land acquisition. This aspect of the ruling sparked controversy and led to appeals from both the defendants and the implicated lawyers. The Court of Appeal suspended the execution of the judgment on April 10, 2013, and ordered a retrial, which began in 2016.

It was during this period that 258 of the 401 claimants opted to pursue a consent judgment, brokered and supported by NETPIL, ActionAid Uganda, and FIAN Uganda. “We finalised the consent on 10th February 2022. It was a difficult but necessary decision for those 258,” said Kange. The remaining 143 claimants chose to continue litigation, and their case remains ongoing at the Mubende High Court.

Compensation Trickles In

After intense lobbying and documentation efforts—including the collection of national IDs, letters of administration, and verification of identities—compensation payments began in January 2025. In total, Shs2.58bn was released to some of the first families under the negotiated package.

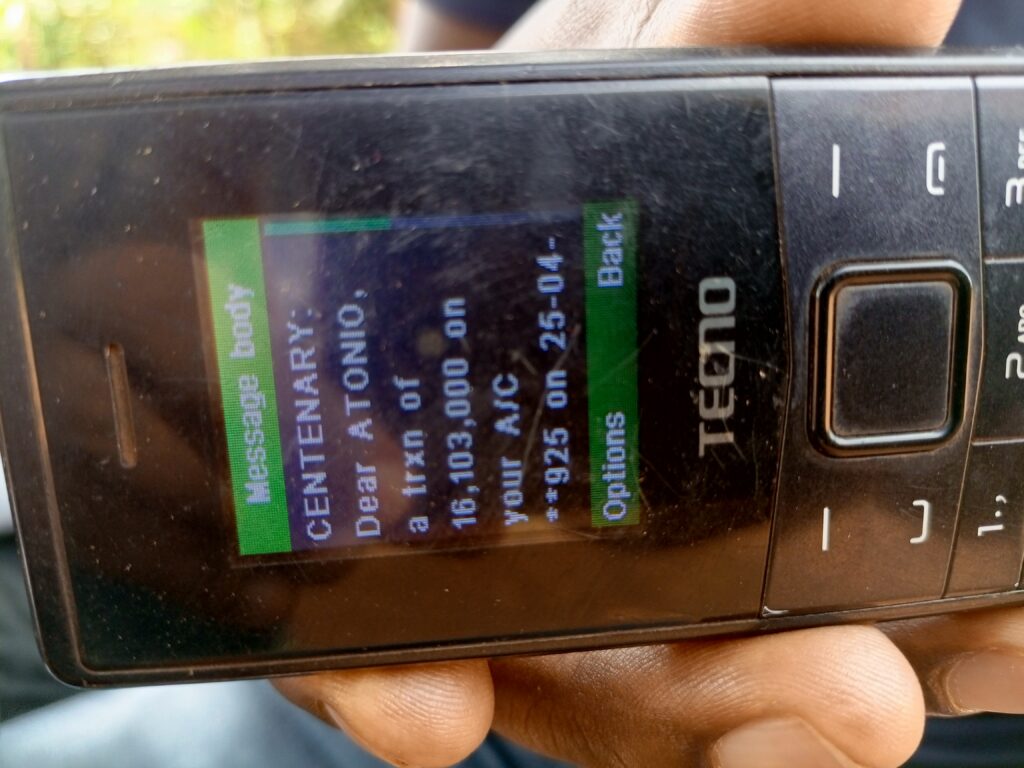

According to Kange, the first payments were disbursed on 23rd January 2025, with most recipients receiving their money between 24th and 25th January 2025. A second batch of payments was processed on 2nd May 2025.

“As of 13th May 2025: 102 claimants have been fully paid, 56 claimants are in the final stages of payment, 19 claimants had payment delays due to bounced transfers and 4 more are being resubmitted for processing,” she revealed.

Tragically, 84 claimants died before receiving compensation. Letters of administration were secured for only five deceased, enabling direct payments to their families. For the remaining 79, the government has agreed to deposit their money into an escrow account managed by the Office of the Prime Minister, to be accessed once valid letters of administration are presented.

Lives Changed, Futures Rebuilt

For many beneficiaries, the money has come too late to reclaim what was lost, but it has offered a chance to rebuild. For many recipients, the compensation, though modest compared to the land’s current value, has enabled them to restart their lives.

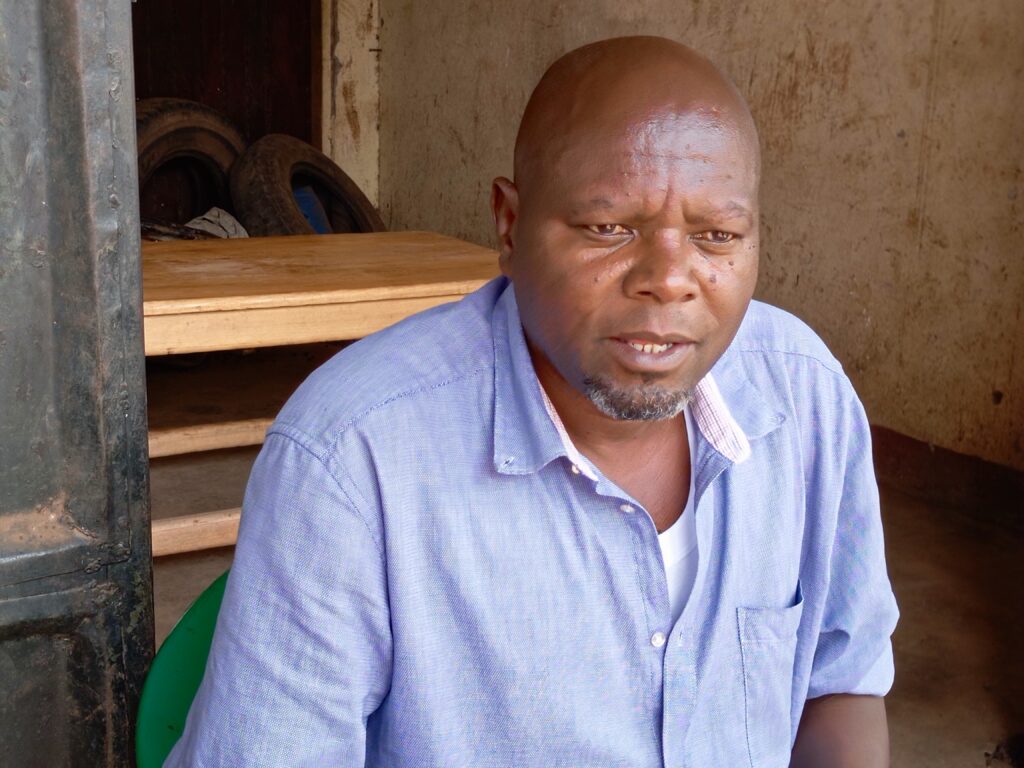

Antonio Mugerwa, a resident of Kijunga, received Shs16m in compensation and is constructing rental units and cultivating coffee. “We accepted the money and chose not to cry over spilt milk,” he notes.

“In 2005, I bought 5 acres of land at just Shs300,000. Today, half an acre costs Shs1.5m,” he adds, highlighting how inflation and delayed compensation robbed many of better opportunities.

Ssebuwato “Balaba” Patrice, the former LC1 Chairperson of Kitemba village, received Shs14m. He used the money to buy a residential plot in town and restart his cattle business. “I didn’t bring the money to eat—I brought it to restore what I had before the eviction.”

At 53 years old, Namubiru Margaret, a resident of Kasambya Cell, Kijunga Village, received Shs1.2m in compensation for her portion of the taken four acres of land. “I plan to start a small poultry farm with this money,” she says with a spark of determination in her voice.

Charles Bagarukayo, now 53, was a young and ambitious farmer when the Kaweri eviction struck in 2001, stripping him of his 85-acre farm, his first home, and over UGX 70 million worth of investments.

When partial compensation eventually came, Bagarukayo acted decisively—purchasing five acres of land, installing a Shs8m underground well with a modern pumping system, and constructing rental houses that now generate monthly income. “I turned pain into profit,” he says, proud of what he has rebuilt.

Not all were as fortunate. Ssango Bonny, also from Kijunga, received Shs4m, which he says is too little to buy new land. “If we had received this earlier, it would have changed more. But we are thankful to at least be seen.”

A man of many roles—father, farmer, and husband of two wives (the third wife left him), Bonny owns several small plots where he grows coffee, trying to rebuild what was lost. However, he is left weighing his options, unsure whether to invest in land again or find another way forward.

At 86 years old, Nakatte Maria Ntonino is among the oldest surviving victims of the Kaweri land eviction. She was around 62 years old when the incident happened. She remembers the smoke more than the shouting—the way the flames licked through her thatched roof, the sound of people screaming, running, stumbling over each other in fear. The experience was not only traumatic but nearly fatal—she became gravely ill, bedridden, and unable to flee.

Nakatte received Shs3m in compensation, which she used entirely on medical treatment. Now frail, Nakatte spends her days managing illness, without any opportunity to rebuild or develop her life. “I am sleeping,” she says softly. “No other development. Just sickness and hospital.”

Restoring a Community’s Spirit

Meanwhile, community groups like the Naluwondwa Playground Committee are using their compensation for collective development. With Shs40m received, they aim to restore a vital youth stadium destroyed during the evictions.

“This field gave our young people purpose and direction,” said Balongo Frederick Bikwalila, vice-chairperson of the committee. “This stadium was our pride. We were young then—now we’re forty. It’s time to prepare the ground for the next generation.”

Nakavubu Magdalena, the treasurer of the restoration committee, emphasised the stadium’s value to young girls. “Instead of girls wandering into dangerous spaces, they would come to the stadium and play football.” “We pray that the council moves very well to restore the youth field so they can love themselves again.”

Likewise, the Kitemba Munno Mukabi Farmers Group, led by Chairman John Kyamani Muhwezi and Secretary Amos Rubarema, stands as a powerful example of resilience, unity, and grassroots organisation.

As Secretary of the group, Rubarema says before the eviction, the group farmed a communal plot, sharing resources and working together to ensure food security for their families. “From the ashes, we reorganised and collectively bought new land and began farming again,” he states.

The group did not wait for compensation to rebuild; instead, they began savings activities and income-generating projects, encouraging one another to remain hopeful. Today, their group has expanded from 50 to 70 members, including youth and children of the original members.

Their savings and loan scheme is flourishing. With Shs20m saved and an estimated Shs40m in total group assets, they continue to operate a revolving loan fund that supports members in need. “We are farmers. We play as one. We save together. We borrow and support each other,” says Muhwezi, the group’s chairman.

Voices That Refused to Be Silenced

Baleke Kayiira, the Leader of Madudu Evictees, who still awaits compensation, remains a steadfast voice for the 143 families still pursuing litigation. From his quiet village home in Kitemba, Kayiira recounts a turbulent 20-year struggle that has left families homeless, children exposed to disease, and livelihoods destroyed.

“I am a victim of land grabbing. My great-grandfather settled on this land. My grandfather was born here. My father was born here. I, too, was born and raised here. My children were born here. This land is part of us,” Kayiira explains.

The land in question—Block 99, parts of Blocks 100 and 103—covers over 12 square miles. The land was allocated for a plantation project in cooperation with the Ugandan government. However, according to Kayiira, no fair compensation, resettlement, or genuine consultation ever took place.

“We didn’t want just money. We wanted land too. What happens when the money is gone? Land is life,” he states, vowing to continue the legal battle and grassroots resistance against corporate land grabbing in Uganda. “We were called squatters on our land. But we will not be erased from history. We are not weak—we are fighting for our children’s future.”

Solomon Musindi, on the other hand, one of the affected community members, in a twist of fate, was appointed Assistant Resident District Commissioner in 2024. He calls on the government to be proactive. “If you must acquire land, compensate people fairly. Don’t humiliate them. Don’t destroy their lives.”

He, however, acknowledges Kaweri Coffee Plantation’s positive contributions to the district, noting its role in job creation, infrastructure development, and increased local revenue, even as resettlement and compensation issues remain a concern.

A System Still in Need of Reform

While compensation is a welcome step, lawyer Kange highlights that challenges remain. “There’s no interest or inflation adjustment. Payments are based on 2001 values. Some received as little as Shs90,000.”

The complexity of acquiring national IDs, opening bank accounts, and verifying documentation has proven overwhelming for rural residents. Travel costs for verification trips to Kampala have consumed much of the compensation for some.

“I cannot access the compensation for my late husband’s land because I don’t have the letters of administration,” Margaret, a widow, explains. The process to obtain those letters demands Shs630,000, a sum she currently cannot afford.

Still, Kange remains hopeful. “It may not be full justice, but it’s a form of closure. We now have a cluster of grateful people who have something to show for their 20-year struggle.”

A Message from ActionAid Uganda

Esther Kisembo, Project Coordinator at ActionAid Uganda, reiterated the organisation’s commitment to land justice. “This was a case of the poor suffering at the hands of the rich. People were chased from their homes, became food insecure, and lost everything. That’s why we stood with them.”

She added: “We’re grateful to the Government of Uganda for committing to these payments in the 2024/2025 financial year. This moment is not just about compensation; it’s about restoring dignity and trust in the systems that protect citizens.”

Looking Ahead

The road is not over. Hundreds still await resolution. The community hopes for continued government support, finalisation of all pending claims, and reforms to ensure future land acquisitions are just, transparent, and respectful of human rights.

As Deputy RDC Musindi put it: “If land must be acquired, let it be done with fairness. Don’t destroy lives.” Lawyer Kange, who has been at the heart of the legal process, also hopes the remaining claimants receive their dues quickly “so communities can finally heal and move forward”.