Dr Jimmy Spire Ssentongo, a Cartoonist and Lecturer, is the face of online exhibitions dominating social media and aimed at exposing potholed city roads, the struggling health sector, and security issues, among others.

It all started while he was driving home one evening from work and a driver in front of him hit a huge pothole on Balintuma Road and badly damaged their vehicle.

“The idea started with a tweet, which many could have taken for a joke. Their doubts were not far from mine. For I was only throwing a stone into the bush,” he wrote in The Observer.

He continued: “One of the things that have come up strikingly in the exhibitions is that there are so many Ugandans burning with pains and frustrations for which they have no outlet. The exhibitions seem to give them a ray of hope and alternative ways of speaking.”

His exhibitions saw the president order the immediate release of Shs6 billion for filling potholes and has since been venerated as the new face of social justice.

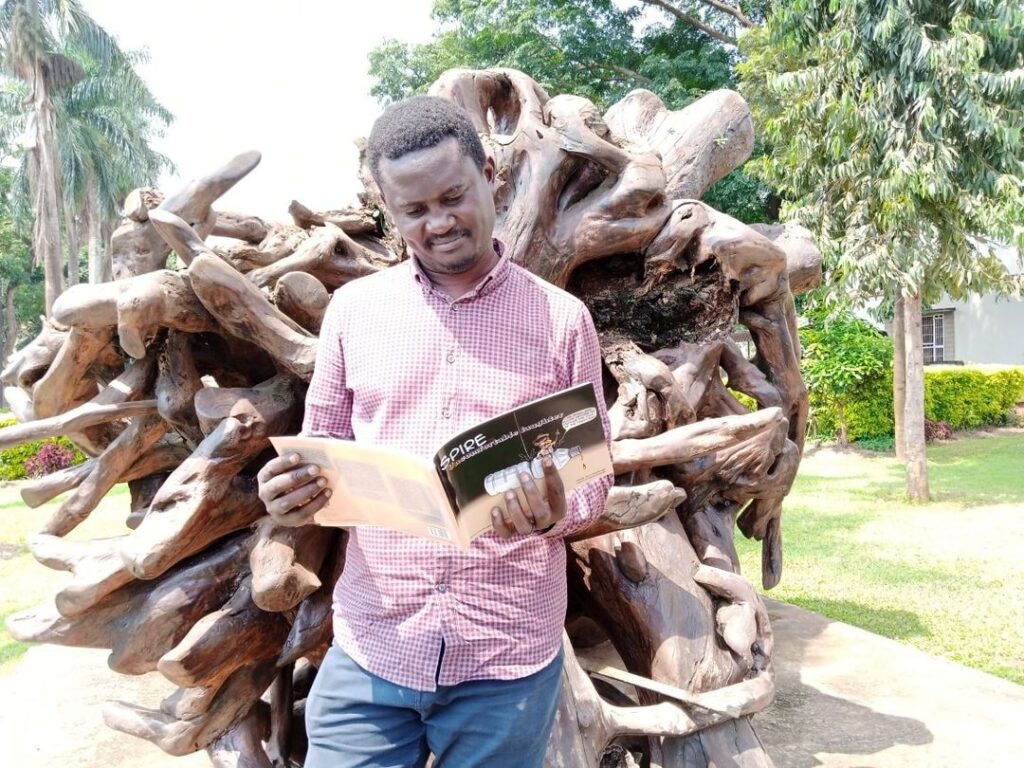

The man behind the exhibitions:

You know him as Spire, a name that is also signed on his hilariously satirical political sketches, under the label “Spire Cartoons” on Facebook.

Ssentongo heads the Centre for African Studies plus research and publication at Uganda Martyrs University and teaches Philosophy at Makerere University.

As a self-trained artist, he also works as an editorial cartoonist and columnist for The Observer – a weekly independent newspaper.

This is what he told SoftPower News editor, Rogers Atukunda, in a lengthy chat at Makerere University sometime back.

Here are the excerpts:

QN: The last time I checked, you were teaching philosophy at the university, right? Now, how did a philosophy lecturer decide to draw cartoons?

Laughs. Drawing cartoons is more of a passion. Art is a talent that you can practice whether you have studied it or not. I studied art for only two terms (S.4 second and 3rd term). I don’t have any qualifications in art or cartoon drawing. It’s my passion. Cartoons are a strong way of packaging messages you think are sensitive or delicate, especially in a society that doesn’t read that much. I have been manoeuvring with cartoons since school. You want to say something to teachers; you draw a cartoon and pin it on the noticeboard. That is how I contribute to society.

Qn: When did you draw your first cartoon?

I don’t recall. Maybe S.1 or S.2 but my first published cartoon was in a short-lived paper by Katz. He was a Daily Monitor cartoonist and an architect. He came up with a paper called “Cartoon Theatre”. It would collect cartoons from different cartoonists. He organised a Cartoon Drawing Competition and the award was publishing the winning cartoon. So, I sent in my cartoon which became my first to be published. It was around 2005.

Qn: How did you become a cartoonist and columnist for The Observer?

I contacted The Observer in 2006 while doing my Master’s degree at Makerere in Ethics and Public Management. I just walked into The Observer’s offices and told them I wanted to draw cartoons for them. They asked me for samples. I sent them about three. One was of a marabou stork standing on an electric wire. It was a time of so much load-shedding. One marabou stork was telling the other “eeh, it used to be quite dangerous to stand on these wires”. That was my first cartoon to be published by the paper. Since then I have been drawing for them for 14 years now.

Qn: Most of your cartoons are from current events, is there a specific philosophy behind them?

The basic message behind them is justice. What inspires me is fighting against injustice whether in/by government or other societal aspects. Laughing about these things sometimes makes people think twice about their behaviour. I often do cartoons to ridicule someone who is doing something inappropriate; I ridicule or lampoon them to make them change their behaviour. Cartoons in newspapers are generally not paying. It is my passion for the work and my desire to contribute to society that drives me.

Qn: Are your cartoons against the government? They only touch itching incidences in politics. How would you convince someone that this is constructive criticism not just shouting against the government?

Do the cartoons depict reality? Do they pick on real issues? You may not find cartoons from me that just pick on the government for its own sake. It is in the nature of cartoons not to praise but critique through satire. You rarely find cartoons that praise the government. They try to raise concern and debate about issues. It is not something I would say is unfair to the government. I think the biggest problem is those who praise the government without showing them where they are wrong. The other issue is that my cartoons seem to be favourable to the opposition. It’s not to praise them but because the opposition is mostly suppressed. I don’t just sing their praises but I cite out where they are being unfairly treated. If the government changed and the opposition took power, my cartoon direction would change. I may favour them now but if they go into power, I can’t promise to favour them then. That is why I can’t join any political party.

Qn: What could you say has been the impact of your cartoons in your 14-year-long career?

It is difficult to tell whether my cartoons have had a direct impact. I can’t chest-thump now but when I hear people talking about the cartoons or see them in different fora, I know the message is moving. Even those that I’m addressing, I see some of them responding, saying the cartoon was unfair– it means the message has been delivered. When I see change coming after, I can’t tell whether my cartoons contributed to it or not. There are many other players that are part of the entire picture.

Qn: Tell me about your new project.

The project is about animating Ugandan folktales for educational and entertainment purposes, because these stories are dying out. I’m working with people from the Literature Department at Makerere University and Musinguzi Studio that animates the popular “Katoto” character. My role is to discuss the different perspectives of the stories we are trying to animate.

Qn: Would you be interested in drawing cartoons for animation, that is, when the Ugandan film industry catches up?

Animation is very tasking. It is something I have always wanted to do but it’s quite demanding. The process to see one figure moving is a lot of work. As a lecturer, I have to teach, read and publish. That makes it a little hard for me to go into animation. I support it entirely but delving into it won’t be now.

Qn: I have always loved the cartoons you draw about Beti Kamya. They are the most hilarious. How do you pick the cartoon concepts that make us laugh right away?

It is different ways depending on what you are addressing. Sometimes you get ideas in unexpected ways. Sometimes I’m taking a shower and an idea pops up. So, I shower very quickly and then go and note on paper. Sometimes you have to sit and think. Strangely, cartoons that are loved by people are the ones that don’t take me a lot of thinking. Beti Kamya, I find her quite intriguing in her contradictions, especially since she has kept changing sides from government to opposition and then back to the government. She is also an interesting character to draw. I enjoy drawing her face (laughs) and elongating her mouth (more laughter).

Qn: Let us discuss your cartoons about the president. They started with sharpening the head to wearing a signature big hat. What’s with the bottle of mineral water always hovering above?

Actually, the pointed head was started by Snoggie, a veteran cartoonist based in the US who draws “Snoggie’s World for Uganda”. With time, Museveni changed his dress code and now puts on a hat. The bottle is partly inspired by Jonathan Shapiro, a South African cartoonist, known as Zapiro. He used to draw then-President Jacob Zuma with a shower on his head. When Zuma was being tried for rape, he told the court that he didn’t contract AIDS because he immediately took a shower after the act. Zapiro started drawing him with a shower overhead. It angered him so much that he went to court demanding that Zapiro removes the shower from the head. My inspiration for the bottle started from there, specifically from the president’s irrigation initiative in Luweero. For many people, this was a funny and weird thing that in this century and age, the president is out there demonstrating how to irrigate with a bottle. The bottle helps me to ridicule him and, wherever the bottle is, it represents his influence or hand in different situations. The bottle moved from water to yellow content. Likewise, when I draw Inspector General of Police (IGP) Okoth Ochola’s yellow nose, it shows the “yellow-isation or NRM-isation” of the police – that the police are acting partisan and on the president’s orders. Wherever you see the yellow nose, you will know this is Ochola, just like people see the t-shirt of Balaam Barugahara and know it is him.

Qn: Tell me about your book. Why did you choose to make a collection of the cartoons?

I started on it somewhere around 2010 but abandoned it. It requires a lot of time and resources. Printing a full-colour book of that volume is rather expensive. Towards the end of last year, I saw a call from Kuonyesha Art Fund for funding art projects. I applied and they considered me. They are partially funding it but this made it much easier. Now a selection of my cartoons can be found in one place as a compressed critical history of Uganda in various aspects that could perhaps only be told in more than 1000 pages of text.

Qn: Why did you choose the title “Uncomfortable Laughter”?

While the cartoons might come across as funny, the issues they speak about are generally uncomfortable. Many are actually painful – things that perhaps would have killed us in frustration if we did not find a way of laughing about them.

Qn: What is the purpose of the book? Who do you intend it for?

I want it in as many places as possible as long as it can initiate and inspire debate. I haven’t thought about it going to schools but it may inspire kids to draw. My main target is human rights organisations, all possible change agents, and art schools; someone can learn one or two things from these cartoons or get inspired. I want the content to make people think about our country and what we can do to improve it, not only laugh.

Qn: Why this specific choice of the book cover?

The bottle is central to my cartoons. What happens in the country currently and the difficulty to change it rotates around the bottle holder and how police engage in partisan politics. It summarises the role of the president, and the police, and how public perception and agency are shaped.

Qn: Who is Dr Spire?

This is not an easy question to answer because a person is many things. The question only solicits what they choose to tell you.

Qn: Then let us talk about teaching. Is it a calling or something you must do?

Teaching is something I always wanted to do, specifically university teaching. I’m interested in teaching that generates knowledge, not just knowledge transfer. I want to add something to what I’m teaching. It is something I do out of love although there is something I don’t like about our current university set-up. At the university, to be promoted, you need to do some scholarly writing yet this practically contributes little to society. My cartoons are in a way educational and they help me teach society. Philosophy helps me interpret events and human behaviour. So my cartooning and teaching are complementary engagements.

Qn: How do you see Uganda’s current political set-up? What will our future be like?

In terms of the future of Uganda, I would say it is uncertain. There are all signs to confirm that. I used to be a fan of Museveni or say a fanatic. I did many drawings of Museveni as a child. I was infatuated with his person and had a lot of hope for him. Over time, I started realising that he may be taking us back to where he claimed he came to pull us out of. He is convinced that he can do so much for Uganda and no one else can do it. He has made the whole country and the whole project unsustainable because everything has been made to rotate around him. What happens when that person is no longer there? A more hopeful project would be where one person makes a contribution while building other entities like institutions and even individuals. You need to inspire and groom people to join politics to build the country but instead, most of those around him are negatively inspired into bootlicking, which shows he has no will for making this society grow. There is so much anger, especially among the young people. What happens if this anger finds expression? With one spark, everything can crumble. Peace becomes meaningless if it’s not sustainable. This society is like an egg, anytime it can break. We can have genocide in Uganda. You hear the ethnic sentiments, I know some are propaganda, but many people are angry.

Qn: Through your cartoons, have you seen a curve of Museveni deviating from original intentions?

I had thought of one specific cartoon to depict that but I keep putting it off. I wanted to show some sort of evolution process. Like they say we came from apes going up to a standing man. But Museveni started from crawling to standing and is now going back to crawling.

Qn: Have you been reproached by the government? First, how do you get away with drawing such cartoons about Museveni? Secondly, what went wrong during quarantine?

What happened to me in quarantine had nothing to do with my cartoons, I believe. People thought I was being tortured for my cartoons. Not because this government isn’t capable of that, but I think I was just caught in the middle of their panic and incompetence plus corruption in handling quarantine. We were the first group and it was clear they were not prepared. I was not harassed in any special way. There was no sign of being targeted. Apart from these ministers and those connected who sailed through, the experience was worse for everyone else in quarantine. It wasn’t the government trying to do something to me in revenge.

On government threats, strangely, I haven’t got any. They have been relatively tolerant of cartoonists. I only heard of one case of the late Daily Monitor cartoonist Moses “Mozeh” Balagadde who was questioned for drawing a cartoon in The Independent Magazine. I also heard that Monitor cartoonist Chris Ogon has been threatened for drawing a cartoon about the first son Gen Muhoozi Kainerugaba. Generally, you would have expected worse. I haven’t been warned or called by anyone except a few regime sycophants who will send you messages complaining. I haven’t received any threat from the president, army, police or minister. Maybe they are still on the way. I have drawn cartoons of the first lady Janet Museveni and heard people saying I was risking but nothing has happened.

Qn: So, would you say Museveni has been liberal with his critics?

I think Museveni is mostly concerned about people who go out of their way to seriously threaten his seat. But I have seen the government trapping critical people who don’t even have those intentions. I know journalists who have been purged and pushed out of the system like Charles “Mase” Onyango-Obbo, former Editor of Mail & Guardian Africa and former Managing Editor of The Monitor and Daniel Kalinaki, Nation Media Group General Manager in charge of Editorial, who wrote a book about “Kizza Besigye and Uganda’s Unfinished Revolution”. I wouldn’t say Museveni has been entirely liberal with everyone.

For the cartoonists, maybe they have just decided to ignore or they are waiting. The other possibility is that cartoonists are not easy to catch using the law. You notice I just write something vague or generic in my cartoons. Unless the cartoonist is reckless enough to label the cartoons, it is not easy to pin them to anything. All my captions are carefully chosen. If you are to follow the law, it becomes difficult to catch a cartoonist unless you decide to use brute force.

On getting away with “Museveni cartoons”, people usually ask me “Don’t you fear?” If anyone tells you they don’t fear [I have a family and kids], they wouldn’t be genuine. But you just choose to do what you must for society. My conscience is clear that what I’m doing is not wrong and I have to do my duty as a responsible Ugandan citizen. But the fear is always there.

Qn: If someone reading your book, asked you to close your eyes and pick your favourite cartoon, which one would that be?

Actually, unfortunately, the cartoon I considered to be not my best but one I’m so attached to, is that of the president milking a skinny cow (Uganda). It so happened that at the end of this book project, I realised I had not included it. I felt so bad. I somehow assumed the designer had included it. I only realised this after printing the book. Initially, I had wanted to make it the cover cartoon. The second one is also not there—one of the man with a hat raping the Constitution. But omitting that one was deliberate. I had mixed feelings about drawing it, and whether to include it. Not about what the target would think but whether it’s gross. I didn’t want to depict him in the very act but in the process of that, say, removing his trousers. Some people may not focus on the message but on the depiction of sex. Some just get excited and say “Museveni is here having sex with the constitution”. So, I decided to leave it out, even at the time I drew it, I saw moralists saying it was not appropriate. Age limit time was the time when I was most active in my cartoon drawing. Cartoons on the age limit cover almost a quarter of the whole book. So I could leave the other one out.

Qn: Have you considered designing a website or personal blog to immortalise your work?

Someone volunteered to do it for me. They are working on it. I will surely follow it up.

Qn: Tell us a little about your personal life.

I’m married with kids. My wife is also a lecturer here [Makerere]. I come from Masaka. I come from a family of nine [five brothers and three sisters]. I was born at Nsambya Hospital, and by then, we lived around Kikoni [Makerere]. My father was the District Executive Secretary (DES) of Masaka at the time of his death, way back in my childhood.

I went to Kimanya Blessed Sacrament Primary School and then joined Bukalasa Minor Seminary. My mother wanted me to become a priest. I was at Bukalasa Seminary up to S.4., where I was expelled in the first term. By then, there was this Chic Magazine in the 90s. It was popular for stories on social life. Peter Ssematimba [now Pastor and owner of Super Fm] had a column on the last page where he taught people about things like kissing etc. In the middle, they would have a full-page picture of a lady in a bra and knickers only. In a seminary, this was considered pornographic. One day, we were sent home for school fees and a colleague brought back four of the magazines. The next morning, there was a search and whoever was found with a copy was expelled, including myself. I completed S.4 at Kimanya S.S., where I had the chance to study art for two terms. Then one of my uncles, Fr Ben Lutaaya, who was a missionary priest working in Tanzania took me there to join Uru Seminary in Moshi for S.5 and 6.

After, I joined the Apostles of Jesus Major Seminary in Nairobi, Kenya. I did a Diploma there and a Bachelor of Philosophy from Urbaniana University (Italy). After my Bachelor, I decided to leave and come here to Makerere where I did a Master’s in Ethics and Public Management. I then got a teaching job at Uganda Martyrs University, Nkozi and later did a Master of Science in Education for Sustainability from London South Bank University on Commonwealth scholarship while at the same time pursuing my PhD from the University of Humanistic Studies, Holland. I finished my PhD in 2015. That is basically it.

Qn: How do you balance teaching at two universities?

At Nkozi, I’m no longer seriously teaching. I mostly do administrative and editorial work. It is only here, at Makerere, where I teach. It is crazy balancing all I do, but such is the life I live. It almost works all through.

This interview was first published in December 2020.