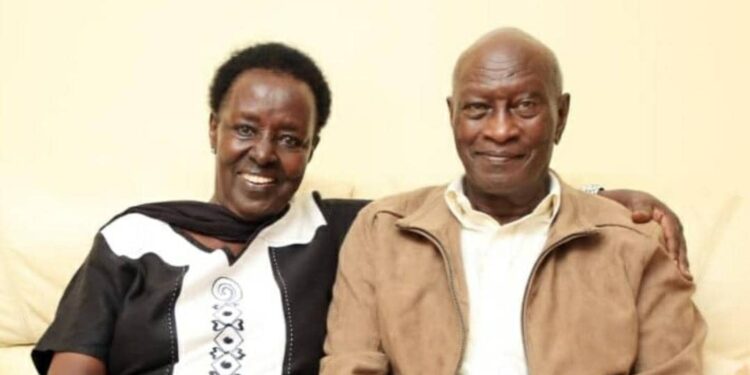

Sam Baingana, 90, tells it all in his “90 Good Years Memoir”. The Book tells of his uncertain childhood due to the loss of his mother at an early age and going on to graduate from Makerere. Baingana moved on to a life of glamour as a Foreign Service officer. He was the Permanent Secretary of the Foreign Affairs Ministry when Idi Amin usurped power.

Below, Dennis Katungi shares an edited extract of Sam Baingana’s pioneering entry into the Foreign Service well before Uganda’s Independence.

In 1961, I was selected to be among the pioneer officers of the Ministry of External Affairs [as it was then known]. I was sent to the London School of Economics LSE in the UK, together with Leonard Mugwanya and one Ndawula, to study International Affairs and Diplomatic Practice. After my course, I was attached to the British Embassy in Paris as an intern and spent a month doing Foreign Service practice. My colleagues received different attachments. Among the other students I remember at LSE was Yash Tandon, a Ugandan Asian.

Just before Independence, in September 1962, the doors of Uganda’s Foreign Service were opened, and I, among others was there as a pioneer. They included Henry Kyemba, Paul Etyang, Prince John Barigye, Stephen Karamagi, William Matovu and Eldard Wapenyi. John Kinuuka and others would join afterwards, in 1964.

Although we, the pioneer Foreign Service officers [FSOs], were younger men with diplomatic training, Prime Minister Milton Obote selected more senior men as his first Ambassadors to Uganda’s missions abroad – men who had been tried and tested in the colonial government. These included Bazaarabusa who had been an education officer in the colonial government. He was posted to London as Head of Mission. Apollo Kironde, a grandson of Sir Apollo Kagwa and formerly a Minister in the colonial government was posted as Ambassador to the United Nations in New York and Eng. Kamba, an engineer in the colonial government was posted as our first ambassador to India. Matiya Lubega would later be posted to open our mission in Accra, Ghana.

The first Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs was a Briton named Richard Posnett. He served a few years before being replaced by Zirubabeli Bigirenkya. Richard Posnett would return to Uganda as a British High Commissioner many years later, during the Presidency of Yusuf Lule. At independence, Prime Minister Milton Obote retained for himself the External Affairs portfolio and appointed Sam Odaka as his Deputy Minister. I started off at the rank of Assistant Secretary and was designated Chief of Protocol. This was the period of Sir Harold Macmillan’s “Winds of Change” which were blowing across Africa, and Independent African states were being born in quick succession. After Ghana in 1957, Nigeria followed and then Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, Zambia, Malawi etc, in that order.

Our first missions abroad therefore were New York, London, Washington, New Delhi, and later Cairo. These Missions reflected the foreign policy priorities of Obote’s government. Cairo during the years of Abdel Nasser, and New Delhi were important capitals in the Non-Aligned-Movement.

By the time of Uganda’s Independence in 1962, the idea of an East African Federation [EAF] was being seriously considered by Kenyatta, Nyerere and Obote. The British too were in favour of an EAF but were careful not to give the impression that they were pushing us into one. Nkrumah, however, was opposed to an EAF. He believed in a Union of all African States and saw regional groupings like EAF as a stumbling block. It was clear that he also had ambitions of becoming the president of the United States of Africa, which he feared would be undermined by an East African Federation.

At the first major conference of its kind, thirty-two independent African States met in Addis Ababa in May 1963 to establish a framework for African cooperation. Africa’s political giants of that era were all there: Sekour Toure of Guinea, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Leopold Senghor of Senegal, Abu Bakar Tafiwa Balewa of Nigeria, Houphet Boigny of Ivory Coast, among others. In his speech, Nkrumah made an impassioned plea for a United States of Africa. Of thirty-two countries present, only four voted for Nkrumah’s proposal, and Uganda was one of them. Obote had fallen under Nkrumah’s sway. This Addis Ababa conference birthed the Organisation of African Unity [OAU] and also endorsed the idea of regional federations. So, the following month, June 1963, Kenyatta, Obote and Nyerere met again in Nairobi and issued a statement committing themselves to an East African Federation before the end of that year. But while Nyerere and Kenyata appeared fully committed to the idea, Obote having aligned himself with Nkrumah, was half-hearted about it. It died a natural death. At about this time, Matiya Lubega was sent to open a mission in Accra Ghana.

In 1964, Permanent Secretary Richard Posnett’s contract ended. He was replaced by Z.Bigirwenkya, and I became Under Secretary. I also became the first Chief of Protocol and Marshall of the Diplomatic Corp. Later that year, we opened a mission in Cairo and Obote posted Paulo Muwanga there as Ambassador. Paul Muwanga a specially elected member of Parliament was prevailed upon by Prime Minister Obote to resign his seat in order that Kakonge could replace him. Kakonge had recently lost the position of Secretary General of UPC to Grace Ibingira at the famous Gulu conference of 1964 and had convinced Nyerere to prevail on Obote to appoint him to Parliament. In return, Obote asked Muwanga to resign his seat in Parliament so that he could appoint Kakonge in his place, and we found ourselves having to find a slot for Muwanga in one of our diplomatic missions.

Paul Muwanga mismanaged the Cairo Embassy and I would later, as Permanent Secretary, go to Cairo to audit him. I found the Embassy in a mess but was lenient with him, and thankfully so, because many years later, when he was Vice President in the Obote 11 government, I would come under suspicion of subversion by the government, and Paul Muwanga would prevent my arrest and possible execution. This story is told in another chapter. Partly as a result of the mismanagement of our Cairo mission, a new policy came into force in 1969 to end the practice of posting non-career diplomats to our missions abroad. At that point, Paul Etyang would be appointed to London; Prince John Barigye to Bonn; Mark Ofwono to Cairo; and Matiya Lubega to Moscow.

“90 Good Years Memoir” will be in bookshops soon.